Scrolling down

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870708

The SmartCulTour Toolkit was created by, for and with all partners in the SmartCulTour project. Our close collaboration with the six SmartCulTour Living Labs has made it possible to develop, test and evaluate the tools and process presented in this Toolkit. Consequently, we are confident that the tools presented do not just make sense from a theoretical point of view but also that they lead to meaningful results. This toolkit is presented in two formats for optimal adoption in professional practice, education and academia. First, it is available online as a guide and training aid for using the tools in practice through www.smartcultour.eu. Second, it is available as this extensive pdf booklet with more background information and sources (downloadable as deliverable 7.3 on www.smartcultour.eu). We sincerely hope it will support you in rethinking and redeveloping sustainable cultural tourism.

Bert Smit, Mira Alhonsuo and Ella Björn (authors & editors)

The SmartCulTour Toolkit

Bart Neuts – KU Leuven - project manager SmartCulTour

Tourism is an important economic sector in the European Union, contributing an estimated 10% to EU GDP and employing more than 26 million people in 2019. Within Europe, a significant portion of tourism is at least partially culturally motivated, with estimates placing the number of primary culturally motivated visitors at around 11% of the total market, and primary, secondary, and accidental cultural tourists at around 40%. While cultural tourism is therefore an important visitor segment and strong economic driver, it can be recognized that there is an uneven distribution of both cultural heritage and cultural tourism across European regions. Many regions have a (very) high presence of cultural assets whereas in other regions their presence is marginal. However, there are also plenty of regions that generate a significant number of overnight stays but are relatively poor in cultural heritage, just as there are many regions rich in cultural assets that are hardly touched by tourism development.

Large regional differences and unbalanced tourism development has given rise to a new research agenda that focuses on the potential development of peripheral tourist areas. The increase of experience-oriented cultural tourists, who seek to immerge themselves in ‘authentic’ local life has created new opportunities for such destinations. The SmartCulTour project therefore aims to support development in regions with untapped potential by providing process flows to identify, set up and monitor interventions in the cultural tourism field.

At the same time, these cultural tourism development efforts need to be framed within the local social and environmental context in order avoid the pitfalls of unsustainable development and contribute to resilient communities. This is also reflected in the definition on Sustainable Cultural Tourism, as developed by the European Commission, Directorate D – Culture & Creativity, as one of the initiatives for the European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018: “Sustainable cultural tourism is the integrated management of cultural heritage and tourism activities in conjunction with the local community creating social, environmental and economic benefits for all stakeholders, to achieve tangible and intangible cultural heritage conservation and sustainable tourism development.” A critical element of this definition is the integration of the ‘local community’, which also follows the principles of self-determination.

The primary goals of this SmartCulTour Toolkit is therefore to provide local communities and policy-makers with information and tools to start a collaborative process. Rather than top-down decision-making and strategic formulation, the project wishes to help the integration of local stakeholders in the full process of tourism development. Within the project, and through various tools developed and tested in SmartCulTour, we would like to help regions in their tourism development plans and create real partnerships, delegation of power, or even full stakeholder control.

Since the 1960s, tourism has increasingly been identified as a potential engine for regional development, mainly focusing on the potential economic effects of foreign income generation and employment. However, in an attempt to achieve economic growth, environmental and social impacts were at times neglected. The last two decades, the consequences of a singular economic focus have become clear, with the destruction or diminishment of natural values, the loss and commodification of local cultural identity, or merely the strain on local resources due to ever-increasing visitor numbers. Even though these issues are not purely the effect of past planning decisions and policies, local destination management has surely contributed to current issues in certain tourist areas.

By recognizing the limits of a purely growth-focused strategy and the negative impacts it has created in some destinations or specific tourist attractions, new, developing regions can learn from others and take alternative paths in order to attract a visitor economy that supports prosperity, rather than just profit. An essential aspect for finding a balance between the social, economic and environmental sphere is the integration and cooperation of a variety of stakeholders who might each hold different interests, opportunities, and specific knowledge.

While traditional participative approaches have increasingly relied on consultation, in such situations the power balance between decision-makers and consultants remained uneven, while also the choice of consulting partners itself could be influenced by prior expectations. At the same time, it has to be recognized that power delegation and more active partnerships are complex to manage and the loss of control by policy makers might be seen as problematic since they often still hold accountability of the final project.

We therefore realize that the context of a destination needs to be taken into account and, depending on the type and vulnerability of resources, the scope and size of tourism, the maturity of the destination, and the established policy framework, different participative models and supportive tools are required. The SmartCulTour Toolkit therefore discusses how different methods for co-design of cultural tourism can be adopted.

Through the different approaches to destination development and the tools and training aids presented in this document, we hope to support local actors to identify collective opportunities, reach synergies, and develop successful interventions towards future development in order for cultural tourism to contribute substantially and sustainably to local communities throughout Europe.

Bert Smit – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Mira Alhonsuo – University of Lapland

Developing sustainable cultural tourism as part of its wider socio-techincal environment is complex. There is no single approach or tool that will be able to tell why, how, what and when to develop interventions that allows local stakeholders to flourish. Just like building a home, different tools are needed at different points a time. We don’t use a paintbrush to drill holes, nor do we use a saw to place the windows in our home. Designing and “building” a sustainable cultural destination therefore also needs a set of tools, each with its own purpose with an instruction on why, when and how to use it in combination with other tools.

The SmartCulTour project developed and tested tools specifically for participatory and bottom-up approaches to destination development in six different Living Labs. Research was also done on how to combine tools for different purposes, which are explained in the chapter on Design process crafting. Understanding which approach fits your destination and the purpose you have defined for bringing together local stakeholders is important in selecting the right set of tools and using them in an order so that each tool delivers output that informs one or more of the next stages of your design process. This toolkit provides you with 14 different tools. Each tool is explained in a similar way and provides instruction for use, including relevant sources, examples, templates and powerpoints.

We expect and hope this toolkit will help destinations in developing sustainable cultural tourism.

Split, Croatia

a reflection

Scrolling down

Utsjoki, Finland

Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Split living lab is a translocal scale living lab that involves stakeholders from three bordering suburban communities. The goal of the living lab is to raise cultural tourism awareness in the area to bring these suburban, underdeveloped neighbourhoods to their tourism potential. With a multi-stakeholder approach, the living lab ensures that all decisions and interventions are 100 percent co-created by stakeholders. The living lab is initiated through the SmartCulTour project call. However, prior to the living lab being established, the University of Split has already built close ties with the local stakeholders to join forces in developing tourism strategies and planning, as well as involving in other tourism marketing activities. Thus, the existing stakeholder network has provided the Split living lab with an advantage by having a stable yet active pool of participants joining the living lab. In total, there are six formal living lab workshops and three informal meetings. Due to COVID-19, the first three meetings were held online and the rest of the meetings were held within the campus of the University of Split. The living lab is composed of a variety of stakeholders, including the tourist board, Croatian chamber of commerce, regional authorities, tourism entrepreneurs, cultural associations and local community representatives. These stakeholders all have a converging interest, which is to speed up the cultural tourism development in Split. Each workshop is created in accordance with the progress and the needs of the living lab discussion. Following the double diamond approach created in WP 7.1, the workshops have utilized many SmartCulTour tools to stimulate discussion and increase interactivity between stakeholders. Tools such as SmartCulTour Game, Opportunity tree, House of quality, SWOT analysis and SmartCulTour dashboard are used throughout different workshops and have yielded great open innovations. In particular, the SmartCulTour Game is able to enable stakeholders to view tourism issues from different perspectives, creating a mind-opening experience for stakeholders. Furthermore, the House of quality is utilized in the workshops to find out the most suitable interventions within the Split living lab. The final two interventions are as follows:

- Raising awareness of cultural heritage and the potential of community-based cultural tourism to inspire local community development through developing two promotional videos focused on the valorisation of the intangible heritage of Split. The promotional videos are planned to be distributed on different social media channels to reach different targeted audiences.

- Co-designing tailored education programs with local stakeholders and offering the programs via the FEBT lifelong learning centre.

Although these interventions are specific to the living lab content, they are not specifically place-based. Moreover, these interventions have the ability to scale up and have a sustainable lifespan.

Although two concrete interventions are found in the Split living lab, it is not without major challenges. The Split living lab, has experienced limitations with regards to the workshop's time frame due to prolonged holiday periods in the winter and summer months. Moreover, public cultural institutions such as museums are underperforming within the living lab due to ongoing resistance to changes and social capital limitations. Lastly, limited financial and human resources directly impact the choices and outcome of the interventions.

Despite the known challenges, the Split living lab has successfully founded two realistic and attainable interventions due to the relentless dedication and involvement of all stakeholders. Moreover, the Split living lab has successfully built a bridge between academia and the local community to allow further collaboration to happen in the future.

Rotterdam, consists of two community-scaled living labs, focused on further developing, promoting and attracting tourists to visit these two neighbourhoods. Rotterdam is the only location within the SmartCulTour project that organizes two living labs involving two different neighbourhoods, namely the district of Hoek of Holland and the district of Bospolder-Tussendijken. Both neighbourhoods’ living labs emphasize a bottom-up approach involving multiple stakeholders, especially including local residents and entrepreneurs in the co-creation process. Rotterdam, also a special case within the SmartCulTour project, has an existing living lab established called the “Living Lab of Rotterdam” prior to the SmartCulTour project. Thus, the existing living lab is able to provide Hoek of Holland and Bospolder-Tussendijken living labs a competitive edge, as both neighbourhoods are able to utilize the synergy of the existing stakeholder’s network and have an actual physical space dedicated to the living lab. In the first living lab meeting, Rotterdam stakeholders decided to focus on developing the southern part of the city, and therefore, the two neighbourhoods, namely the district of Hoek of Holland and the district of Bospolder-Tussendijken are chosen to be included in the project. These two neighbourhoods are labelled as up-and-coming districts, each with its unique characteristics and tourism potential. In total, six living lab workshops are hosted in a mixed format, consisting of online and on-site meetings. These living lab workshops are held in the respective neighbourhoods to maximize the participation rate of the local stakeholders. Representatives from the municipalities, DMOs, entrepreneurs and local inhabitants are actively involved in the two neighbourhoods’ living lab to discuss current issues, challenges and future opportunities. To ensure the themes of the workshop are relevant, the living lab manager and their team plan each workshop according to the recent topic discussed in the previous meeting. Different art-based tools are used during the workshops to increase stakeholder engagement, as well as to stimulate fruitful discussions. Art-based tools such as the SmartCulTour Game, System Mapping, Visitor Flow Mapping, Personas, House of Quality, Ideation Washing Machine and Destination Design Roadmapping are utilized to aid the process of intervention creation. Through utilizing the above art-based tools, both Hoek of Holland and Bospolder-Tussendijken living lab can come up with ten place-based potential interventions to improve the tourism offerings and the attractiveness of their neighbourhood. The final intervention of the SmartCulTour Rotterdam living lab is to create a report to present to the municipality of Rotterdam and other stakeholders involved in the development of the concerned areas. The report will serve as a proposal, including recommended interventions created by the two neighbourhoods’ living lab, that will serve to guide and uphold the sustainable development of both neighbourhoods respectively.

The SmartCulTour Rotterdam living labs face different challenges that ultimately lead to the inability of carrying out concrete interventions in real life. First, both neighbourhoods’ living labs have a hard time retaining steady stakeholder representatives. Most of the stakeholders, especially entrepreneurs and local residents attended the workshops on an impromptu basis and are not willing to commit to attending multiple workshops. Thus, the potential interventions suggested have resulted in more of a top-down than a bottom-up approach. Moreover, the general attitude of the participants is more passive and is highly reliant on the living lab organizers to take the lead and provide guidance during the whole process. Furthermore, due to both financial and political constraints, the municipalities of the two neighbourhoods, as well as other important stakeholders are not willing to take on more responsibility to ensure that the potential interventions would be developed further. All of these challenges above hindered the progress of the feasibility testing of the potential interventions suggested.

Although the outcome of the SmartCulTour Rotterdam living lab differs from what was expected, the benefits of the two neighbourhood living labs are apparent. The SmartCulTour project created an open and reflexive platform for these two neighbourhoods to face their tourism challenges and discuss future opportunities. It also created a stronger connection between local stakeholders, especially between the municipality and the local entrepreneurs. Thus, the journey of the SmartCulTour Rotterdam living lab does not end here, but it is only the beginning for both neighbourhoods to identify their challenges and to find out possible sustainable tourism solutions to increase their tourism attractiveness. It might be a long road till some of the interventions can be carried out successfully, but in the meantime, it is a good start to raise cultural tourism awareness and establish a network between stakeholders within the neighbourhoods that might flourish and thus lead to future collaborations.

Although the Utsjoki living lab successfully came up with and has partially implemented some of the interventions, the living lab faces some challenges. Firstly, the utilisation of Sámi culture in tourism may have negative impacts on the local communication due the history of misuse and misrepresentation of Sámi culture in tourism industry. The Sámi Parliament has established core principles for sustainable Sámi tourism and efforts have been made in Utsjoki to encourage the local tourism companies to develop sustainable cultural tourism products. Secondly, although fifty percent of the Utsjoki population is indigenous, the Sámi culture is underrepresented. In the end, only one stakeholder who participated in the Utsjoki living lab has Sámi background. Moreover, the hybrid format living lab sessions evidently impeded the flow of the discussion, as a moderator must be involved to summarize the discussion alternately for both the online and on-site groups. Lastly, the physical distance between researchers and the local stakeholders hindered the participation rate of the living lab, as well as the progress of the final intervention implementation.

Despite the challenges, the Utsjoki living lab not only has successfully come up with four concrete and realistic interventions to promote sustainable tourism for the area, but it has also created a possible platform for stakeholders to reflect and discuss about Utsjoki’s sustainable tourism challenges and future directions. Furthermore, the Utsjoki living lab has also provided the opportunity for local stakeholders to create stronger bonds and connections among each other that could foster future tourism corporations.

The Utsjoki living lab is a community-scaled living lab that focuses on enhancing sustainable tourism in Utsjoki. Moreover, Utsjoki’s living lab is special in its way, as it is the only living lab within the Smartcultour project that involves the voice of the indigenous population. The living lab emphasizes a bottom-up approach involving multiple local stakeholders in the co-creation process and initiated through the SmartCulTour project call. In total, seven living lab workshops are hosted in the hybrid format. Due to the physical distances between researchers and stakeholders, the living lab manager decided to offer workshops in a hybrid format, allowing maximum flexibility for stakeholders to join the meeting either on-site or online. A new living lab location is chosen every time to ensure an equal opportunity for different stakeholders to participate in the meetings in person. The living lab is composed of a variety of stakeholders, all holding different yet important roles. Representatives from the municipality of Utsjoki, Sámi parliament, research institutes, local entrepreneurs, as well as indigenous reindeer herders are involved to discuss challenges, as well as come up with concrete interventions to improve the sustainable tourism of Utsjoki. The topic of each workshop is designed to fit the theme that was last discussed in the previous meeting, to capture a deeper insight into the challenges, and to find potential solutions to the current issues. Stakeholders are also given a chance to vote for what is needed to be discussed in these workshops. Apart from constructive debates and discussions, the interactive workshops utilize different art-based tools to brainstorm challenges and explore possible place-based solutions that suit the living lab context. The Utsjoki living lab follows the double diamond model structure to plan different art-based activities to increase engagement and stimulate the thinking process of the stakeholders in these workshops. Tools such as opportunity tree, placemaking videos, personas, multi-process flow, customer journey mapping and role play are used throughout different workshops and have shown great success. Through the above tools, four final interventions are set for Utsjoki and the main theme of the interventions revolves around the themes of nature conservation and tourists’ education. The four interventions are listed below:

1. “Traces in Utsjoki”: it is a playful way to document different kinds of traces in nature and increase the awareness of the littering problem in Utsjoki’s nature.

2.“Trace in Utsjoki Gallery”: an open source website that allows users to download pictures from different traces and findings from nature. The goal is to spark discussion of which traces are generally accepted and which should belong to the nature.

3. Educational posters and stickers: distributed in different tourist hotspots to educate tourists on how to behave in Utsjoki’s nature

4. Placemaking video of Utsjoki: a film about Utsjoki and the beauty of the Utsjoki nature

One of the main reasons Utsjoki living lab can come up with concrete interventions has to do with the support and involvement of the municipality of Utsjoki, as the municipality of Utsjoki expected the outcome would be able to benefit the local tourism entrepreneurs, as well as the residents.

Training of trainers in Huesca, Spain

One of the main tools that the Labs’ coordinator resorted to is bilateral consultations with Lab Managers, as well as with key Labs’ stakeholders if and when relevant. This approach allowed not only to tailor the way forward to each specific context, but also to ensure the endorsement of selected activities by all stakeholders leveraging local ownership. This was particularly relevant vis à vis participants from the private sector, whose continued engagement in the LLs was highly dependent on their buy-in (as a H2020 Research and Innovation project, SmartCulTour was not equipped with funds to reimburse participants’ time efforts; hence, their involvement was completely voluntary-based). In this light, work under WP6 was very closely linked with WP7’s activities and objectives, especially with regard to the production of art-based tools and service-design methods seeking to maximize stakeholders’ co-design and engagement.

The issue of stakeholders’ engagement and active participation was especially sensitive in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Living Labs kicked-off starting from February / March 2021, in a period in which restrictive sanitary measures were still in place in most European countries, therefore preventing Lab Managers from organizing in-presence meetings.

The difficulty to meet in person led to partial delays in the development and implementation of some activities. In response, hybrid and/or virtual meetings were resorted to, also thanks to the development of online tailored-tools that resulted to be effective and hence potentially fit for purpose even in a future non-Covid-19 context.

UNESCO guided Lab Managers in the inception and establishment process of the Living Labs, notably by organizing a Preparatory workshop for the inception meetings (4 February 2021, online), providing advice and presenting practical tools, as well as developing supporting materials for their organization (template invitation, draft agenda, general PPT of the SmartCulTour project, etc.) and for communication and outreach purposes. From a more strategic point of view, the drafting of Standard Terms of Reference (ToR) for the Living Labs (D6.6) provided the general framework upon which individual LLs have developed specific ToR through wider stakeholder consultations and engagement.

The definition of Standard ToR for the SmartCulTour Living Labs was intended to ensure consistency in the overall approach, LLs’ establishment and operational modalities, implementation and evaluation methodology(ies), thus making the different LLs’ results measurable and comparable among them. In addition, the standard ToR provided guidance to harmonize - to the widest extent possible - the composition, number and balance of participants, typologies of activities, data gathering, etc., setting a common strategic direction for WP6.

Drawing on the Standard ToR, each Living Lab developed its own Specific Terms of Reference (D6.1), based on a template produced by UNESCO in close consultation with all involved Consortium partners.

The information contained in the Specific ToR stem from the outcomes of the Labs’ pre-inception and inception phases, including a context analysis, a preliminary and participatory assessment of needs and priorities, and a scenario planning exercise. In addition, the Specific ToR provide data on the typologies and number of participants to the LLs, their functions and scope, as well as a work plan for their activities in support of sustainable cultural tourism (SCT) development. The Specific ToR have guided the LLs’ work, offering a common ground and understanding of their expected outputs and core activities to both internal and external partners. Due to their abovementioned living nature, the Labs have adjusted their trajectory throughout the project’s implementation, based also on the experience gained and relevant findings, which will be presented in the Final report (D6.5).

Coordination and harmonization among the 6 LLs was further ensured through the organization of monthly online meetings attended by Lab Managers and Consortium partners aiming to discuss the state of advancement of the six LLs, ensure coordination among them and with other WPs, and provide strategic direction and guidance on the follow-up. Such meetings were also key to exchanging experiences among the Labs, leading to the creation of an expert network on the management of SCTL, mainstreaming best practices and critically analysing less successful ones. In addition, two main monitoring mechanisms were set up to support reporting on the LLs’ activities and implemented tools and methodologies, i.e. a template Power Point presentation, to be updated on a monthly basis and presented at the all-LLs meeting, and a form for reporting on each session of the LLs, to be shared with the Labs’ coordinator for timely update.

Given the interdependence between WP6 and WP7, UNESCO supported the organization of bilateral meetings between WP7 leaders and Lab Managers in order to identify the most suitable service design and art-based methods to be used in each Lab, seeking synergies and overall consistency between the LLs’ work plans and the WP7 toolkit. In addition, the participation of UNESCO in bi-weekly meetings with WP7 partners guaranteed smooth coordination and joint planning between the tools and methods produced within WP7 and the LLs. The transfer of knowledge from WP7 to Lab Managers was also ensured through the organization of a Training of Trainers on WP7 tools and methods, which took place from 16 to 18 March 2022, hosted by the Huesca LL.

Stemming from the lessons learnt in the context of the SmartCulTour project, the following recommendations can be formulated for researchers and practitioners planning to establish Living Labs mainly in the context of - but not limited to - a sustainable cultural tourism-related multi-partner project:

- Appoint a local Lab Manager, i.e. a local institution (university, research centre, DMO, etc.) to ensure the day-to-day management of the Living Lab. Local partners have a deeper understanding of local dynamics, and normally can already count on a well-established partners’ network, which facilitates the setup of the Lab spanning identification of potential participants, taking contacts with them, selecting a venue, etc. Also, local institutions may already be aware of existing instances and potential clashes within the local community, thereby being prone to a conflict-sensitive approach and more attentively contributing to the preliminary setting of the LLs’ overall objectives.

- Work in local languages and reduce to the minimum the use of English. Although this is highly country- and context-dependent (with some SmartCulTour LLs facing more serious language barriers than others), working in local languages is more comfortable for the stakeholders, eases communication and puts everyone on an equal footing, creating conditions for more productive dynamics and contributing to an horizontal sharing of decision power among participants.

- Whenever existing, frame the LL into already existing local initiatives / structures, so as to avoid duplication, develop synergies and ensure a more effective and efficient action. However, a careful assessment is suggested vis à vis the objectives of such pre-existing entities, and notably whether open participatory processes are envisaged and all interested stakeholders are available to join. Relying on already existing networks can be pivotal for ensuring long-term sustainability of the Living Lab, which also maximizes the project’s impact in the long run.

- Create buy-in for participating stakeholders in order to boost their commitment and active engagement. This is especially true for civil society representatives and private stakeholders, who tend to prioritize their own interests and businesses over LL’s activities if they do not perceive a clear benefit in participating. Budget allowing, possibilities should be explored to reimburse expenses for participants in the LL, as this may contribute to increasing their overall level of availability and engagement.

- Ensure enough flexibility in your planning and limit the use of standardized solutions to accommodate local needs and desires, as well as to respect the living essence of the Labs and the ongoing nature of the co-designing process. In particular, in the case of projects based on tailored, objective-driven and context-specific approaches, take into account that your envisaged course of action may significantly change if it happens not to be in line with local stakeholders’ wishes. Do not commit on behalf of the Lab prior to having consulted local stakeholders.

- Plan in due advance to ensure that eventual delays on the local side do not impair the overall project’s timeline. Beware that the schedule of local processes, including institutional / official decision-making processes, might be not aligned with that of the project, requiring to strike a balance.

- The Project document is not exact science: normally, project proposals tend to be very theoretical and not to reflect the actual situation on the ground, given an inevitable lack of accurate data and information at the proposal drafting stage, combined with lengthy selection processes and the evolution of the circumstances. Due to their living nature, this aspect can affect Labs more than any other activity of the project, so leave a margin of maneuver and ensure adjustment mechanisms for continuous improvement to review the initial strategy and plans as need be, based on feedback from monitoring.

- Set up an effective and efficient monitoring mechanism, including regular meetings (the frequency can be agreed upon at the beginning of the project), template materials for reporting, etc., to facilitate the centralized management of the LL(s), while ensuring that all actors are on the same page.

- Ensure a clear division of roles and responsibilities among the partners, and especially between the Lab Managers and the leaders of other WP planning to test their tools or to deliver specific activities in the Labs. Ensure also that such division of tasks be appropriately reflected in the project’s budget, and that each partner owns the needed resources to deliver the agreed programme.

- Manage expectations and do not commit if the availability of resources, including financial and human resources, as well as time, has not been attentively considered and assessed in advance. This will help avoid the risk of losing the trust of local stakeholders and, as consequence, impairing their sense of ownership towards the project and its objectives.

- Prior to the project’s end, provide participants with a roadmap / plan of action for the future, in order to help them translate the ideas emerged in the context of the Lab into concrete results. In case the realization of such ideas requires some funding which cannot be provided in the context of the project, ensure that the roadmap includes a business plan for its future, potential financing.

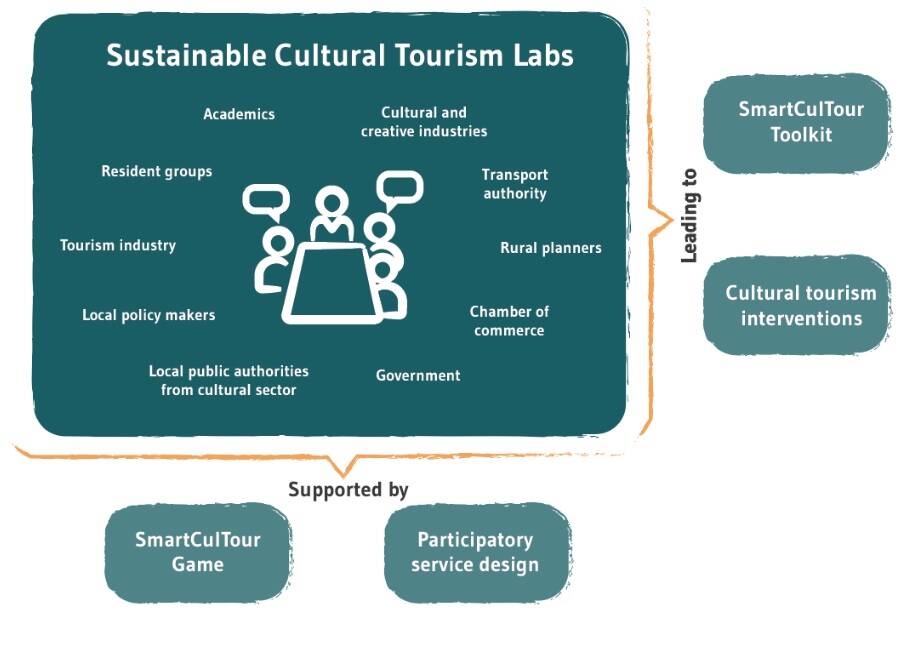

Graphical representation of SmartCulTour Living Labs

In addition to their characteristic as open laboratories, the Living Labs are living entities by their very essence and participating stakeholders may vary according to the topics and objectives of each specific meeting. Also, the goals of the Labs tend to evolve throughout the project’s lifecycle, as a new awareness may arise along with newly discovered priorities.Such dynamic nature also implied the necessity to balance the comparability of results across Living Labs on the one hand with the high degree of flexibility necessary to adapt to the specific circumstances on the other. From a managerial point of view, this was one of the main challenges, as standard approaches could not meet the different contexts’ needs, and therefore place-based solutions had to be identified and developed on a case by case basis.

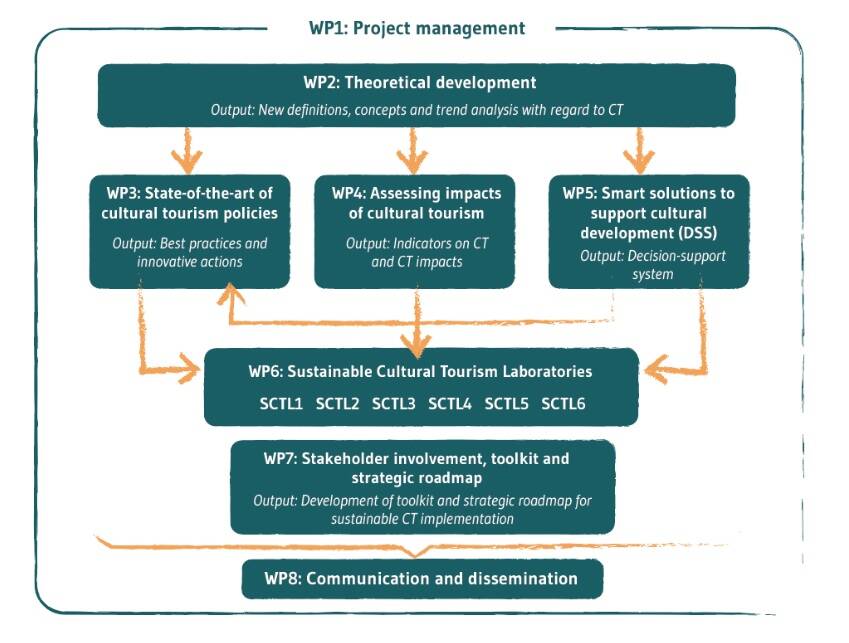

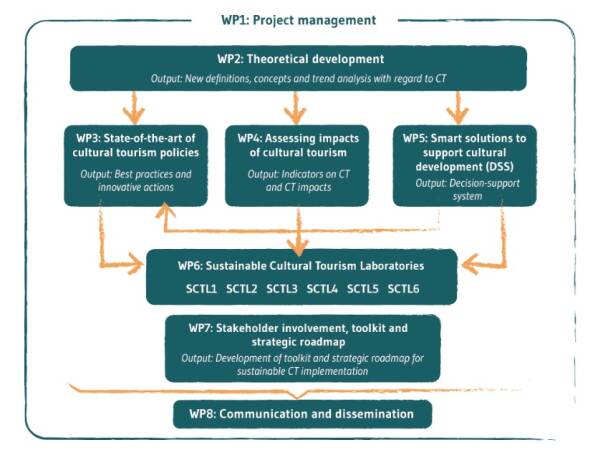

SmartCulTour Work Packages

As leader of Work Package 6 on “Sustainable cultural tourism laboratories”, UNESCO coordinates the six SmartCulTour Living Labs, namely the Rotterdam Metropolitan Region (Netherlands), the Scheldeland Region in Flanders (Belgium), the Utsjoki Municipality in Lapland (Finland), the Huesca Province (Spain), the City of Split metropolitan area (Croatia), and the City of Vicenza (Italy).

The selection of the six (cultural tourism) destinations was aimed at ensuring different geographical and typological coverage, mainly consisting in three destinations having a strong urban / city-based identity, while the other three being located in broader rural contexts.

Map of Living Labs Locations

Such intrinsic differences, complemented with the project’s overall needs-driven and context-specific approach, urged a centralized coordination and continued guidance to ensure, as far as possible, that the six Living Labs (LLs) delivered the agreed tasks in a consistent manner, while adapting the tools and methods developed within the project to their specific needs.

This role was chiefly performed by UNESCO, supporting the LLs since their establishment and throughout their lifecycle in the development of their respective workplans and operational functions, including through tailored capacity-building actions, as well as in the identification of meaningful activities, methodologies, and interventions to be implemented in each of them.

In particular, UNESCO facilitated the coordination of activities in the six Living Labs by improving cooperation, co-creation and co-decision making between relevant stakeholders to support strategic planning, policy development and the identification of interventions towards more sustainable forms of cultural tourism.

This task was particularly important as the Living Labs are the cornerstone of the SmartCulTour project, linking the theoretical with the practical and empirical. The success of the project largely depended on the capacity of the Labs to make the best use of the SmartCulTour tools, while testing and trialling them and thereby contributing to their amelioration and refinement in a two-way process.

The greatest care has been taken to in the preparation of this publication. The authors and editors cannot be held liable in case any information or content has been published incompletely or incorrectly. If you feel your rights have been infringed, please contact Smit.b@buas.nl. We will be pleased to receive any adjustments to the contents.

Emma Kirjavainen – University of Lapland

Costanza Fidelbo – UNESCO

Ko Koens – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Frans Melissen – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Satu Miettinen – University of Lapland

Li Hong – University of Lapland

Simone Moretti – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Jessika Weber -Sabil – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Bart Neuts – KU Leuven

All living lab managers & participants

Bert Smit – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Mira Alhonsuo – University of Lapland

Ella Björn – University of Lapland

Co-authors:

Pictures:

Design:

Editors:

This Toolkit would not be what it is now without the help, support and feedback of:

The SmartCulTour Toolkit was created by, for and with all partners in the SmartCulTour project. Our close collaboration with the six Living Labs has made it possible to develop, test and evaluate the tools and process presented. Consequently, we are confident that the tools presented do not just make sense from a theoretical point of view but also that the lead to meaningful results. This toolkit is presented in two formats for optimal adoption in professional practice, education and academia. First, it is available online as a guide and training aid for using the tools in practice through www.smartcultour.eu. Second, it is available as an extensive pdf booklet with more background information and sources (downloadable as deliverable 7.3 on www.smartcultour.eu). We sincerely hope it will support you in rethinking and redeveloping cultural tourism.

As a destination Utsjoki can be characterised by its wilderness and beautiful landscapes. It is the most northern municipality of the EU with approximately 1,200 inhabitants. People have lived in Utsjoki for thousands of years. Elements of their traditions, culture and history are visible in the entire region as they are closely connected to nature and the Sámi way of life. Tourists are attracted to the region for this mix of nature, culture and traditions. In the SmartCulTour project the focus has been on how to help tourists understand, respect and preserve local nature, culture and traditions. The design process adopted the placemaking tool, personas and customer journey in the first diamond. The placemaking tool focussed on the unique qualities of Utsjoki culture and nature. The personas helped to characterise tourist types and behaviours. The customer journey tool identified moments in time and place where tourists could be taught about nature and culture. In the second diamond, an ideation method (such as the ideation washing machine) and multimethod process flow [SB2] were used to generate and develop ideas to help tourists understand the importance of respecting the mix of local nature, tradition and culture.

Figure 1: The Double Diamond design process (adapted from British Design Council, 2019)

Bert Smit and Frans Melissen – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Design process models are applied in many different fields to help designers structure the activities and stakeholders contributions in the process of designing new or improved products, services and systems. A design process model can be described as visualisation of a process structured around a set of activities needed to create a product, service or system (Smit et al., 2021). Such a process model should provide detailed information on these activities, their intended outcomes, how, when and why they are executed, who should be involved for what reason and in which order these activities should take place.

Discover & Define, Develop & Deliver

Design professionals and academics agree that basically every design process model is organised around a problem space and a solution space. Both need to be addressed to some extent to ensure the design process creates the right solution to the right problem. The British Design Council (2019) has captured this essence of the design process in the Double Diamond process model. In this model the left-side diamond represents the problem space which focusses on the discovery and definition of the problem. The right-side diamond represents the solution space and focusses on developing and delivering solutions and ends when evaluation shows that the design(s) presented is also a solution to the problem defined in the problem space. In itself this evaluation can also be the starting point for a new cycle of the design process. Obviously, smart designers go back and forth continuously between problem space and solution space, adjusting both as they learn more during the process. Therefore, design processes are iterative by nature and the design process is never strictly linear going from problem to solution.

As indicated above a design process model visualises a set of activities needed to create a product, service or system. Consequently, a design process can also be used to design a sustainable cultural tourism system, in which the sum of parts creates the destination and provides input on the developments needed to reach its goals. This toolkit provides a series of tools that can be utilised during activities that together form the design process. Each tool has its own place and function in the process, but just like with doing chores on your home, sometimes you need a hammer and nail and sometimes sandpaper and a paintbrush and paint. Understanding which tools should be used and combined requires understanding the job on your hands and making optimal use of the available resources.

Crafting your design process therefore requires reflection on which knowledge and activities that are needed to develop solutions. This reflection should take place before, during and after the design process. Be ready to adjust the process where needed without losing your goals out of sight.

The SmartCulTour project has worked with living labs in six different destinations to discover how to use and combine design tools in participatory approaches to sustainable cultural tourism development. The choice for a participatory approach was logical given the aim to involve stakeholders in decision making on the role of the tourism system in their neighbourhood, city or region. Each living lab and each destination had its’ unique characteristics and focus, therefore each living lab also adopted its own design process, by organising a variety of activities, using a variety of tools.

Figure 4: Archetype 3 process model

Figure 3: Archetype 2 process model

Figure 2: Archetype 1 process model

Archetype 3: Balancing stakeholder needs in complex destinations: a problem analysis, priority setting and solution focussed approach

The third archetypical process model materialises in complex, mature destinations. Typically, in this destination interventions are needed to alleviate pressure on popular areas while leveraging the potential of cultural tourism for sustainable development of less popular areas. Potentially this could improve the quality of life for all residents and/or contribute to conservation of local tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Destination marketing organisations, key stakeholders in popular areas and tourism & culture policy makers in these destinations already collaborate with each other but are not well connected to residents, smaller cultural organisations & entrepreneurs and hospitality & retail in other parts of the destination. In this sense one could say there is mature tourism system in popular areas but a less mature tourism system in the fringe areas. Moreover as these fringe areas are primarily residential or even industrial, (cultural) tourism is not always seen as a priority or opportunity by local stakeholders or policy makers in adjacent fields such as urban planning, environment, housing and social work. Typical for these situations is that cultural tourism can potentially be beneficial but also harmful for particular stakeholders, for instance for those that would be positively or negatively affected by (further) gentrification of their neighbourhood. Developing sustainable cultural tourism in these areas is a balancing act in which it is important that tourism and tourists actually have a positive impact and are put in service of the local community and/or society. Compared to the other two archetypical design processes the distance between policy makers and local stakeholders is bigger. Moreover policy makers are balancing the needs of the destination as a whole with the needs of neighbourhoods and local stakeholders in a system that is already under pressure.

As a designer your role is to navigate between those stakes and stakeholders to identify scenarios through which stakeholder goals can be reached with available resources and capabilities. It is likely that this process will need a design team rather than a design facilitator as you need knowledge on local stakes and stakeholders, knowledge on participatory design, knowledge on local tourism and knowledge on sustainable cultural tourism. A key aspect of the activities the design team should incorporate in the design process is creating trust and understanding between participating stakeholders. Each stakeholder has their own perception of what is needed, what is important, and what cultural tourism could or should do. As a designer your focus should not necessarily be to reach consensus, but rather to identify the boundaries within which interventions are possible. For this reason the activities in the first diamond need to focus on having stakeholders understand why they agree or disagree, what their goals are and where their red lines are. Moreover, the stakeholders need to understand the decision space of the people involved, so that solutions developed can also be implemented. The second diamond can then focus on developing interventions that fit the neighbourhood context but also contribute to the wider city or area within the limitations of the decisionmakers.

In the SmartCulTour project the Rotterdam Living Lab has been an example of this approach. Tourism in Rotterdam is growing rapidly, putting pressure on the liveability of the city centre. Simultaneously, Rotterdam is experiencing pressure in housing market and inequality in social and economic wellbeing of citizens. Therefor the city has chosen to slow down tourism development in the centre and further develop tourism in the urban fringe but only if it benefits the residents and entrepreneurs. Tourism should make Rotterdam a nicer place for those already living there.

The design process adopted in the Rotterdam living lab used several activities to explore the local contexts of different neighbourhoods and to create empathy and trust between stakeholders. In order to create transparency of the process, the design process itself was also developed with participating stakeholders. This resulted in the selection of activities and tools. Moreover this exercise delivered insights in who should commit to participate in the different activities. This allowed policy makers to share their view on their long term goals and neighbourhood representatives to share their insights, worries and ambitions on short and long term. Tools adopted to share these were exploring dashboard data (e.g. overnight stays, review data, employment rates), Q-sort methodology, system and visitor flow mapping and understanding stakeholder perspectives on possible future scenarios through playing the SmartCulTour Game and Ideation Washing Machine. Prioritisation of and decision making on possible interventions were facilitated amongst others through the dynamic house of quality and tourism destination design roadmapping

Archetype 2: cultural tourism development as a means to an end: a priority setting and solution focussed approach

The second archetypical process model materialises in destinations with a scattered tourism offer consisting of for instance accommodations, attractions and heritage sites. Local stakeholders are aware that by themselves they have limited attractivity but as a region they can offer an interesting mix of activities and stories for a diverse group of tourists. Local stakeholders do not necessarily know each other personally or each other’s stakes, but there is consensus that collaboration could be a step forward, not just for tourism but also for quality of life in the region. Tourism in these destinations is (potentially) an important element of the local economy and livelihood. Often, the regional destination marketing organisation or a regional government takes the lead in creating synergies between stakeholders. In this process model, a number of activities is needed to clarify and define the problem space, but an equal amount of activities or energy is needed to generate relevant solutions. As designer or facilitator your role in this process focusses creating enthusiasm and trust between participating stakeholders, while staying close to their everyday reality. Moreover, as designer you need to orchestrate the activities and decision making in such a way that stakeholders see their needs and ideas reflected in the vision, goals and policies of (other) regional actors.

For this type of process working with a designer that is able to guide the activities in such a way that they result in designs that fit within the requirements of regional policy makers is recommended. Simultaneously the designer needs to select tools for the activities that collect the wealth of tacit and explicit knowledge of local stakeholders to create the fit between regional goals, local needs and being attractive for tourists. It the SmartCulTour project the Scheldeland and Huesca living labs have been examples of this approach. Both destinations include several municipalities with a shared history and heritage (including UNESCO World Heritage Sites) but struggle to attract the visitors needed to support and preserve the local cultural heritage through leveraging the related economic activity and opportunities. The design process adopted in these living labs used several activities to explore the local context and create empathy and understanding between stakeholders. Tools adopted were presenting desk research on local policies and ambitions (for the municipalities involved), exploring dashboard data (e.g. overnight stays, review data), understanding tourist behaviour through system and visitor flow mapping and understanding stakeholder perspectives through playing the SmartCulTour Game. Living lab meetings were held in different locations to emphasize equality between stakeholders and to make sure these stakeholders would see, feel and sometimes taste different interesting areas or products of their region. In some activities participants were put together in small groups working on particular themes, which stimulated the interaction between people that had not worked together before. In the second diamond activities were focussed on generating ideas based on the insights from activities in the first diamond (system maps, visitor flows) and benchmarking wheel and linking these insights to tourist personas and customer journeys. Transparent decision making on interventions was facilitated by using the dynamic house of quality as a multicriteria analysis tool, to select interventions that fitted best with local policies and goals. Moreover by providing feedback using dynamic house of quality, selected ideas for interventions were further aligned with regional goals and local needs.

There archetypical design processes

Looking back we can identify three archetypical design process models adopted in the Living Labs. Each is the logical consequence of the context in which the process was executed. Recognising this context can be beneficial in making decisions on a design process in other destinations focussing on participative approaches to sustainable (cultural) tourism development. We therefore recommend to start using this toolkit by first reading about the three archetypes presented below, to then reflect on which archetype fits your context best and then explore which tools you may want to adopt in your design process.

Design Council (2019). Framework for Innovation: Design Council's evolved Double Diamond. designcouncil.org. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-work/skills-learning/tools-frameworks/framework-for-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond/

Smit, B., Melissen, F., Font, X., & Gkritzali, A. (2021). Designing for experiences: a meta-ethnographic synthesis. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(21), 2971-2989.

Archetype 1: process model for developing destinations: a solution focussed approach

The first archetypical process model materialises in destinations with a limited number of stakeholders that are familiar with each other and their locality, and that already have some consensus on the type of problems they want to solve. Destinations that fit this approach are characterised by their limited complexity in terms of tourist numbers and/or similarity in tourist itineraries. However, tourism is an important sector for the local economy and there is some urgency to solve a (set of) problem(s). In this process model, a limited number of activities is needed to clarify and define the problem space, so most of the energy can be focussed on generating solutions. As designer or design facilitator your role in this process focusses clarifying the shared objectives and on selecting the right activities to come to innovative solutions. For this type of process working with a designer that is familiar with the local situation and local stakeholders is recommended, so not a lot time is needed to transfer knowledge that is already available and shared in the group of stakeholders. In SmartCulTour, the Utsjoki Living Lab

Scrolling down

Scrolling down

Example picture of a meaningful place.

Expected outcomes

As an output of the Placemaking method, participants have shared a number of interesting stories and videos about the different values, perceptions, memories, and/or traditions of a landscape. These reflect values in cultural tourism as well. Sometimes a small detail or an element of nature can be important for a tourist, other times a big event or a landscape creates value. Sharing personal stories creates understanding and empathy, which can lead to stakeholder engagement.

Lessons learnt

Be creative with this method. There are many ways to experiment it further. You can very well emphasize only audio in your method instead of video or image. You can also ask the participants to bring an important object with them that may have meaning to the place. The participants present themselves through the object and tie their story to a place that is meaningful to them. Try to think about your context of development and what kind of approach could be the most engagement or valuable.

Make sure you have a good internet connection while sharing the materials (especially if you haven’t got all materials before the workshop) or bring the right cables to connect different mobile phones or laptops to the projector.

Sources/References

Lew, A. A. (2017). Tourism planning and place making: place-making or placemaking? Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 448-466.

Othman, S., Nishimura, Y., & Kubota, A. (2013). Memory association in place making: A review. Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences, 85, 554–563.

Richards, G. (2014). Creativity and tourism in the city. Current Issues in Tourism 17(2),119–144.

Richards, G. (2021). Making places through creative tourism?. In N. Duxbury (Eds.), Cultural Sustainability, Tourism and Development (36–48). Routledge.

Rose-Redwood, R., & Alderman, D. (2011). Critical interventions in political toponymy. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 10(1), 1–6.

Materials needed

- Videos or pictures of the meaningful places from the participants

Projector and screen or smart TV or hand-held projector.

Laptop

How to use the tool?

This example is for stakeholder engagement purposes at the beginning of the design process.

As a pre-task:

Ask your participants individually to think about which place in their neighbourhood is important to them? How have they imprinted the place? Is there a nature connection to their childhood, culture and memories?

Ask your participants to go to the place, locate themselves in a spot where the elements of the values, perceptions, memories, and/or traditions on a landscape give meaning to geographic space.

Ask your participants to shoot a 1-minute-long video (e.g., rotate 360 degrees) or take a picture, and after, send it to you. The video or picture will be present in the following workshop session.

In the workshop:

As set up, make sure you have all the videos or pictures in one folder in your computer or mobile phone.

Ask the workshop participants to introduce themselves through their videos or pictures. You can ask them to talk about the place they have chosen, and why it is meaningful for them. Give approximately 1-2 minutes per each presentation, depending on how many participants you have in your workshop. As a facilitator, calculate how much time do you need to complete the task. Use a projector and screen or bigger smart TV to show the materials.

Tip: You can use a hand-held projector for participants to project their videos of a chosen surface, like a ceiling, roof, or wall. The workshop can be also held outdoors where the participants can more creatively choose different surfaces and express themselves by combining natural elements, like rocks, trees, or water, and human-made videos and a projector.

Placemaking method

Values for sustainable cultural tourism development

Understanding the meaning of different cultural, creative and natural aspects of different locations in creating a sense of place

Creating understanding between different stakeholders by becoming aware of their personal values and opinions.

Engaging different stakeholders in the tourism planning process

Creative approaches as placemaking, can increase sustainability by developing the creative resources of places (Richards, 2017).

Purpose and description

The Placemaking method works perfectly as a pre-task and introduction of stakeholders. Also, it is an art-based approach to create more in-depth understanding of a place, culture and values of nature and geography. As an exercise, it can engage stakeholders in understanding the meaning of different places for other people. Thus, the Placemaking method can be used in the discovery phase of the design process to engage stakeholders in the process. Placemaking is recommended especially for archetype 1 and archetype 2 design processes.

Placemaking as a way of thinking and doing can offer new means for the feeling of belonging and develop respect for the natural environment. For tourism purposes, the Placemaking method can be used in different ways. The stakeholders or workshop participants can bring a picture or video of their meaningful place to a workshop, and to introduce themselves and the place through the picture. In this way, the method is used both for stakeholder engagement and introducing themselves, the place and its values. Another way to do Placemaking is to bring stakeholders to a location and do a performative Placemaking exercise there. This helps to feel togetherness and connectivity by involving the senses and building connections to a place, land and nature. Placemaking combined with performativity takes intangible and creative forms. As an ideal outcome, it sets the mindset of participants on the current time and place, with their senses enriched and insights about different values of the presented places in their mind.

Picture of an empty template

Scrolling down

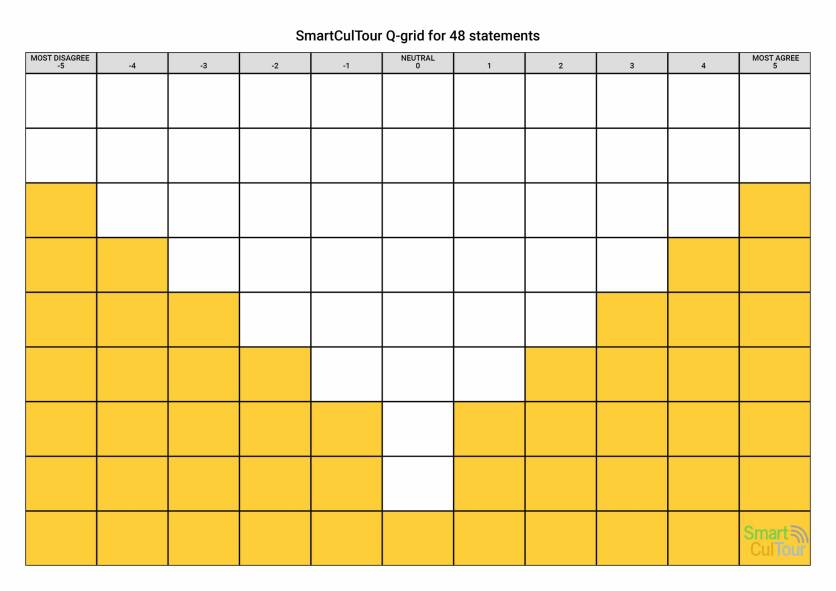

Material needed:

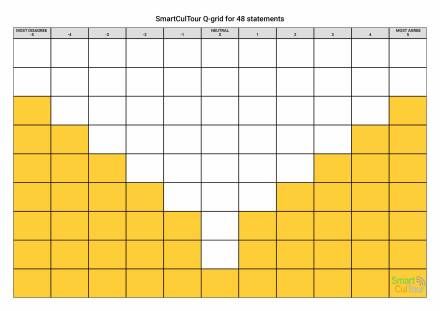

- Q sort grid + statement cards

- A2 paper to write down statements on worldviews

How to use it?

- Invite stakeholders based on stakeholder mapping (6-12 persons).

- Print the templates below (Q-grid and statement cards)

- Have stakeholders sort statements on the grid (strongly disagree - strongly agree) and voice their arguments for their importance. This can be done individually or in small groups. Collect comments and take a picture of the grid. Have participants prepare a short statement on their vision based on the statements they agree or disagree with most.

- Have participants present their Q-grid and vision to each other with a focus on the statements they agree or disagree with most.

- Have participants discuss and reflect on the different views and write down their complementarity, competitive views and contradictions.

Expected output

- Depending on stakeholder diversity between 2 and 4 generic worldviews will be generated during the session. Some stakeholders will feel attracted to one, some to more than one.

- Formulating shared world visions helps stakeholders understand their similarities and differences needed to come to consensus (or disagreement) on future developments.

Lessons learned

Q-sort was adopted in all living labs in the first meetings. From these meetings it became clear that some had a very homogenic group of participants other were more diverse. Stakeholder selection and diversity are key to understand what purposes tourism should serve.

Sources/References

Boom, S., Weijschede, J., Melissen, F., Koens, K., & Mayer, I. (2021). Identifying stakeholder perspectives and worldviews on sustainable urban tourism development using a Q-sort methodology. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(4), 520-535.

Q-sort methodology

Bert Smit & Samantha Boom – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Values for sustainable (cultural) tourism development

- Explore complementary and competitive stakeholder visions on tourism development

- Have stakeholders engage with each other for team building purposes

- Have stakeholders explore and explain impacts of tourism (development) on their livelihood and quality of life

Purpose and description

Stakeholders in cultural tourism development can have highly different worldviews. Understanding and discussing these among stakeholders can support stakeholder engagement, reciprocity and empathy. Q-sort is a mixed-methods methodology employed to identify the main worldviews and related arguments of stakeholders in destination development. The results of Q-sort show the extent to which these worldviews and related arguments are shared, complementary or contradictory for (groups of) stakeholders.

Scrolling down

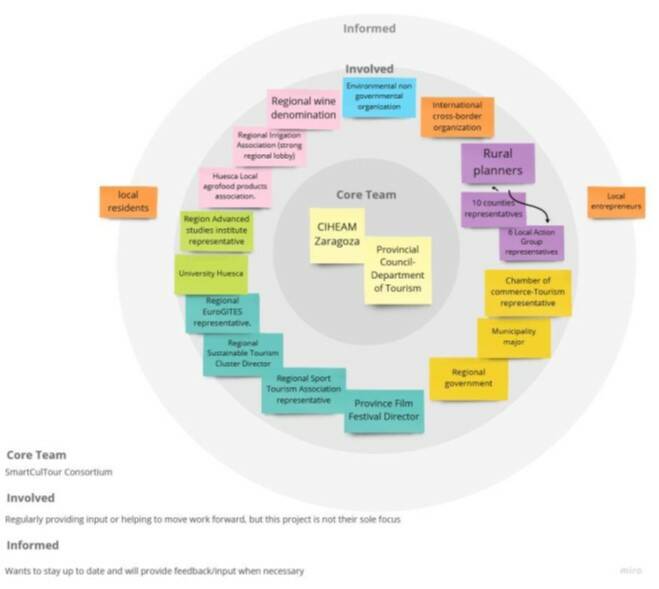

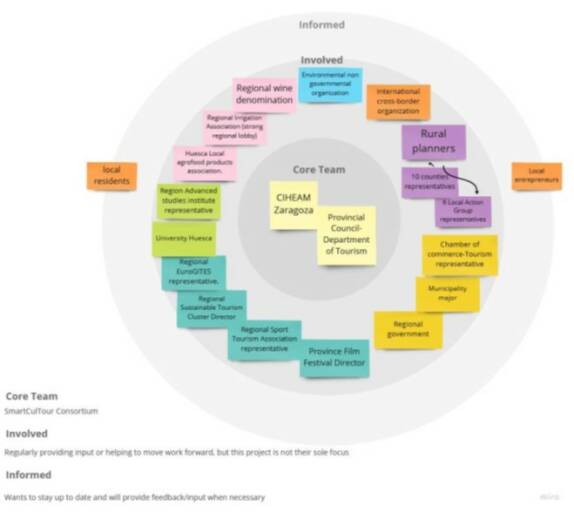

Example stakeholder map, Utsjoki Living Lab

Materials needed

- Large paper sheets

- Sticky notes for stakeholders

- Markers

- Symbols (e.g. stickers) to indicate relationships

Expected output

The outcome of this exercise is a stakeholder (network) map that informs all participants of their shared eco-system and the interdependence of stakeholders and with that their vulnerability.

Lessons learned

In the SmartCulTour project, all living lab managers created stakeholder maps to ensure the right people and organisations were represented in each living lab (see ToR in final chapter of this toolkit) and the different activities executed as part of working in the living labs. In the Rotterdam Living Lab, stakeholder networks were collaboratively identified as part of the inception meeting to determine who should be involved in next activities. This lead to inviting a number of new (types of) participants as a result of determining neighhourhoods of Rotterdam that should benefit from cultural tourism development.

Sources/References

Stickdorn, M. (2014). Service design: Co-creating meaningful experiences with customers. In The Routledge handbook of tourism marketing (pp. 329-344). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

How to use it?

- Create stakeholder maps with three circles on them

- Provide participant with sticky notes

- Have participants collaboratively (in smaller groups if needed) determine the stakeholders and position them on the map to visualise the eco-system

- Cluster stakeholders in networks and indicate their relationships with arrows and predefined symbols

Stakeholder mapping

Bert Smit – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Values for sustainable (cultural) tourism development

- Helps stakeholders understand their role in the cultural tourism system

- Creates awareness of the stakes of all stakeholders influencing and/or affected by tourism development

- Supports ensuring the right stakeholders are involved in or informed about tourism development activities

Purpose and description

Stakeholder mapping is crucial in any participative approach to destination development as it informs those organising the process and activities on who should be represented in the discussion at different points time (e.g. residents, cultural entrepreneurs, tour guides). However, having participants create stakeholder maps in combination with stakeholder network maps helps them understand the complexity of (sustainable) cultural tourism development and the stakes of different stakeholders.

A stakeholder network map categorizes stakeholders in three circles or layers as crucial, important and relevant (or similar terms) for cultural tourism development, with crucial stakeholders in the centre and relevant stakeholders in the periphery. A stakeholder network map (see e.g. Stickdorn, 2014) adds information with respect to the relationships between different stakeholders and the stakes they have in each other (e.g. shared customers, b2b-relationship, shared neighbourhood etc), highlighting their interdependence and vulnerabilities.

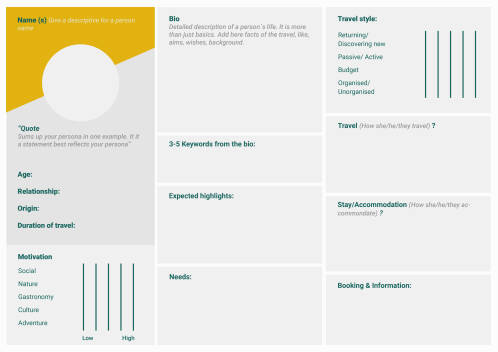

Picture of an empty template

Scrolling down

Materials needed

- A large paper or whiteboard

- Persona template (for print and virtual use)

- Sticky notes

- Pens

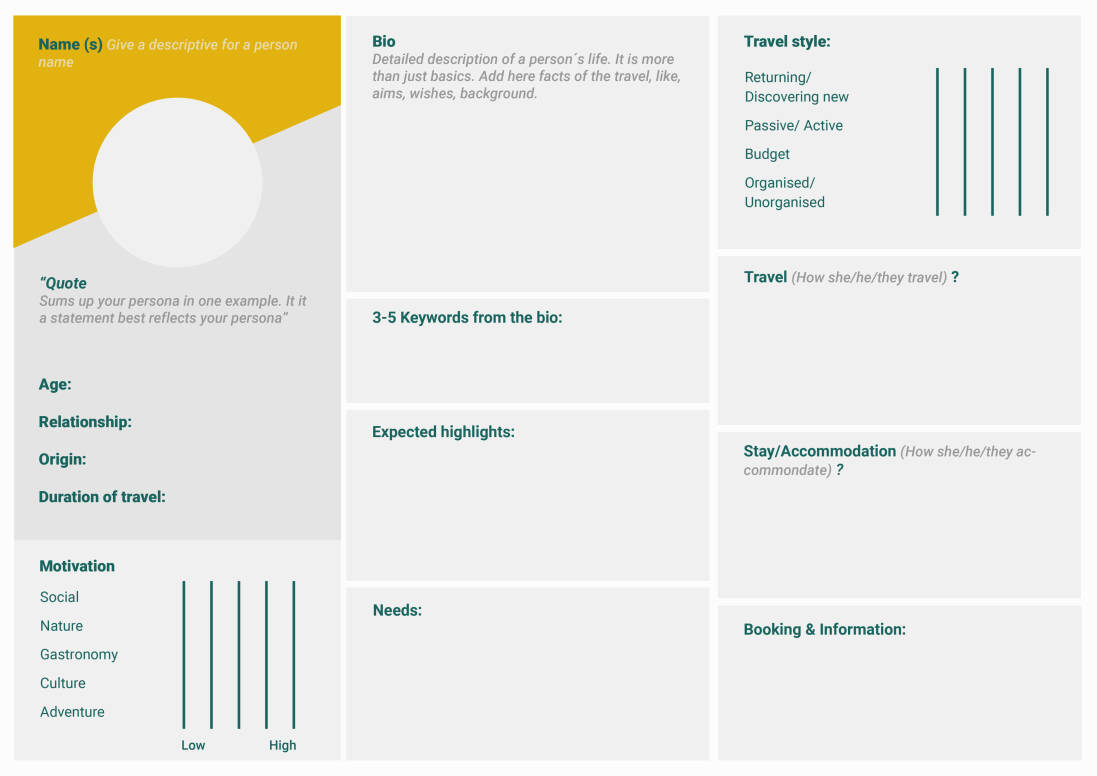

Expected outcomes

A persona workshop ideally results in three to six drafts of personas (physical or digital) which contain information on their needs, wishes, ambitions, values, and (preferred) behaviour in the destination. Each persona is presented on one page including a name for the person, a picture or sketch, and a narrative describing key aspects of context, for instance, demographics, lifestyle, personal goals and behaviour. This information is often supplemented with statements and pictures. It is always good to reflect the personas and critically think if the direction of development still meets the needs of personas, hence, it’s good to keep your personas throughout the design process. Personas can be especially valuable in combination with visitor flow mapping and customer journey.

Lessons learnt

Personas work best if they provide clear statements about their characteristics and are based on real experiences and/or data. Tourist personas can be very valuable in the destination tourism planning process when examining behavioural aspects. Resident and NGO personas can be very valuable in being mindful about the impacts of cultural tourism development. It is important that the personas are not stereotypes or extreme characters, especially concerning ethnicity or gender, but nuanced and realistic persons.

Sources/References

Martin, B. & Hanington, B. M. (2012). Universal methods of design: 100 ways to research complex problems. Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions, 12-13.

Smit, B., & Melissen, F. (2018). Sustainable customer experience design: Co-creating experiences in events, tourism and hospitality. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

Stickdorn, M., Hormess, M., Lawrence, A., & Schneider, J. (2018). This is service design doing: Applying service design thinking in the real world: A practitioner’s handbook. Newton, MA: O’Reilly Media, Inc

How to use the tool?

Start the workshop by explaining the goal of creating personas (for example identifying the key tourist segments and planning sustainable tourism services for them).

If available, provide real user data on (e.g. tourist) satisfaction, behaviour, or needs. The data can be different research data, e.g. reviews, interviews, articles, blog posts and tacit knowledge from the service providers.

Divide participants into small groups, each consisting of three to five participants, and instruct them of creating two personas by collecting and combining commonalities identified in provided data. Give teams approximately 15-20 minutes to go through the data.

Guide participants to discuss the main characteristics, demographics, needs, wishes, and behaviours of the personas to create a narrative of who they are and what is important to them. Provide magazines or stock photos so participants can illustrate activities, values, and places that are important for the persona.

Give a descriptive name for a persona, for example, “Susan Sustainable”.

Have the different groups present and discuss their personas with other participants.

Persona development tool

Mira Alhonsuo & Ella Björn – University of Lapland

Values for sustainable (cultural) tourism development

Understanding the key tourist behavior in the destination

Opening new ideas for sustainable tourism development

Purpose and description

Personas provide archetypical fiction-based descriptions of needs, wishes, and behaviour patterns in a narrative profile of (fictitious) characters representing a real larger group of tourists, residents, users, or other stakeholders. Ideally, personas represent a group of people with similar demographics, values, behavioural patterns and interests, for instance, nature seekers or extreme explorers in a traveling context. Personas are useful for providing understandable information quickly including the main behavioural patterns and features of the certain type of user, tourist, resident, or stakeholder.

A persona workshop ideally results in three to six personas that serve as user-based reference points for the project helping for example defining problems and developing solutions. The personas are created based on the real data from the location. Persona development is ideal for discovery phase in the design process, helping to identifying tourism strategies, policies, products and service needs.

development tool

Scrolling down

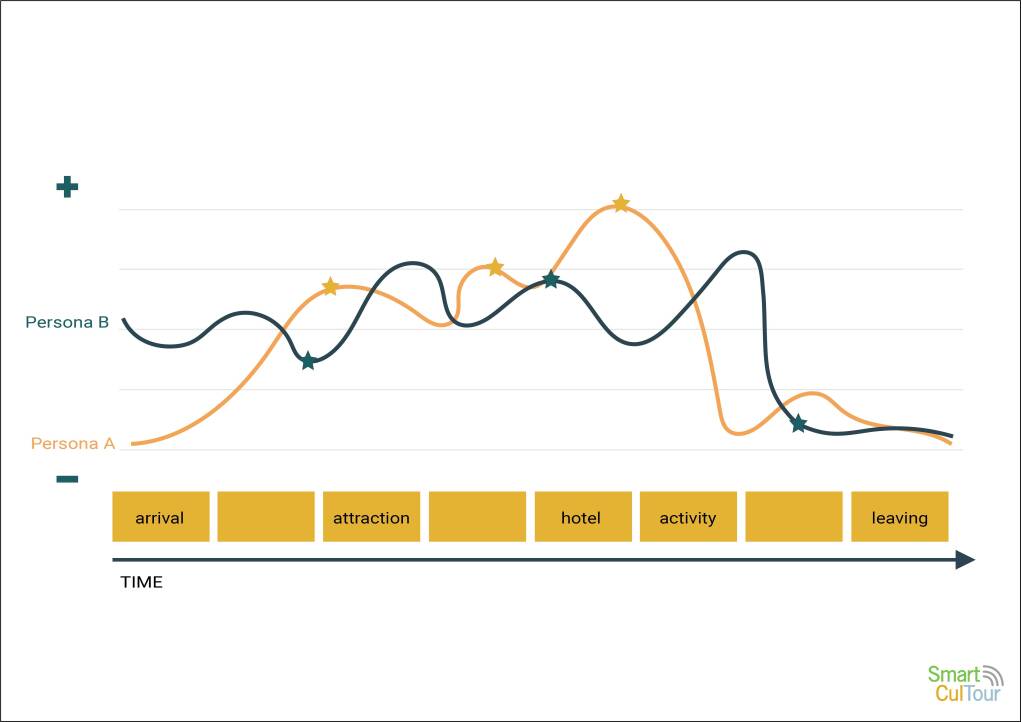

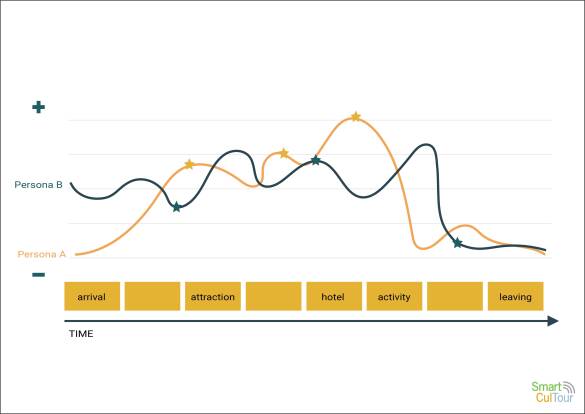

Customer journey, touchpoints and moments of truth

Materials needed

- Post-its, pens

- Flip over charts

Expected output

The outcome is a map with generic journey maps for different tourist types and their evaluation of their activities. Creating these maps helps key stakeholders to share their tacit and explicit knowledge on tourist itineraries.

Lessons learned

The Rotterdam Living Lab benefited from customer journey research executed by the local DMO Rotterdam Partners. Having this research on the table gave tourists a voice in the living lab with respect to their needs and wishes.

Sources/References

Smit, B., & Melissen, F. (2018). Sustainable customer experience design: Co-creating experiences in events, tourism and hospitality. Routledge.

How to use it?

- Ask (groups of max. 4) participants in the workshop to map the activities and touchpoints of specific tourist types or personas on a timescale. Different groups could look into different journeys. Depending on the purpose include the time before and/or after the trip.

- Determine the moments of truth in the journey map that are important from a branding or tourist experience point of view. Add pictures if available.

- Based on tacit knowledge of participants (experience with the tourist type) or explicit knowledge (interview/ review data) fill out the evaluation to understand the dramatic structure. Draw these highs and lows into the map.

- Start a group discussion on activities or touchpoints that need to be changed, improved or added to remove negative point and align moments of truth with high positive evaluations.

Customer Journey Mapping

Bert Smit – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Values for sustainable (cultural) tourism development

- Supports stakeholder understanding of the tourist perception(s) of the destination

- Supports stakeholder understanding of their interdependence

- Provides first insights in improvement points from a tourist perspective

Purpose and description

Customer journey maps provide a time-based overview of touchpoints (or activities) tourists (or personas) participate in or interact with before, during and after visiting a destination (Smit and Melissen, 2018). Each of the touchpoints is accompanied by a customer evaluation (positive or negative). Sometimes these evaluations are segmented for specific customer groups or personas. Together these evaluations form a dramatic structure of highs and lows which can be used to understand touchpoints that customer groups will remember for positive or negative reasons, especially if they coincide with moments of truth (touchpoints associated with the destination brand). This dramatic structure can serve as input for deciding what is going well and what needs improvement, especially when compared to the ideal dramatic structure.

Scrolling down

Example Participatory system map, Rotterdam Living Lab.

Materials needed

- Large printed map or relevant software (e.g. GIS software)

- Instax camera’s or smartphones with relevant software (e.g. polarsteps)

- (bicycle, bus or other modes of transport)

Expected outcomes

- Collaboratively created systems map

- Stakeholders empathizing with each other/ creating bonds

Lessons learnt

- Manage expectations: this tool is to explore problems/ opportunities not to solve problems

- Time consuming for stakeholders, but leads to rich insights and stakeholder bonding

Sources/References

Freitas, R. (2016). Cultural mapping as a development tool. City, Culture and Society, 7(1), 9-16.

Sarantou, M., Kugapi, O., & Huhmarniemi, M. (2021). Context mapping for creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 86, 103064.

UNESCO (2016) Unit 28: Participatory mapping in inventorying. Downloaded from https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/U028-v1.0-FN-EN_Participatory_mapping_in_inventorying.docx Last accessed 29-06-2021.

How to use the tool?

- Determine the geographical area you want to map

- Collect publicly available information on this area

- Select and invite relevant stakeholders (e.g. residents, (cultural) entrepreneurs, tourism policy makers, NGO’s, heritage specialists, historians)

- Select a method to collect data (app, photo diary etc.)

- Have local stakeholders tour each other in the area (this might need some planning) to show highlights and pain points from their own perspective. Let participants take pictures, (audio) notes

- Link the data collected by participants to the map (physically or digitally)

- Present the map (and keep for later use)

Participatory systems mapping

Bert Smit – Breda University of Applied Sciences

Values for sustainable (cultural) tourism development

- Creating understanding between different stakeholders and their perception of (tourism in) their neighbourhood, city or region.

- Understanding the (potential) qualities, consequences and challenges of developing (cultural) tourism in a specific geographic area.

- Collaboratively creating a shared resource for further use in the design process

Purpose and description

Most system maps in tourism are overviews of physical tourism, cultural, historical, and entrepreneurial destination resources relevant to tourists visualised as layers on a geographical map of the destination. However, for sustainable cultural tourism development it can be important to add additional layers of information together with local stakeholders. Such layers could include locations of (historical) events, public transport, planned real estate development and qualitative and quantitative information on the socio-economic situation (employment, safety, visitor pressure, ecology and biodiversity). Creating such a map together provides an important opportunity for stakeholders to share and exchange their perception of the local context and local quality of life. Moreover the map can serve as a shared point of reference for (prioritising) later decisions on interventions.

systems mapping

Scrolling down

Example Visitor flow map, Rotterdam Living Lab

Materials needed

- Large scale prints of the selected area.

- Markers in several colours

- Gps data of visitors if available

- VFM pdf. file

Expected output

The workshop deliver a geographical map with the main visitor flows, linking key attractions and sights, public transport and accommodations

Lessons learned

Visitor flow mapping provided valuable insights in why particular areas were receiving more or less than wanted visitors, especially as a result of changes in public transport options and seasonality

Sources/References

Beritelli, P., Reinhold, S., & Laesser, C. (2020). Visitor flows, trajectories and corridors: Planning and designing places from the traveler's point of view. Annals of tourism research, 82, 102936.

Li, D., Deng, L. & Cai, Z. (2020) Statistical analysis of tourist flow in tourist spots based on big data platform and DA-HKRVM algorithms. Pers Ubiquit Comput 24, 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-019-01341-x

How to use it?